The Rigs of Chapel Ed – April 23rd 1870

Of course I went to Chapel Ed on Good Friday. It was expected by many that I should go and I am always willing to please if I can. A full, true and particular account of all that passed at that celebrated place will be looked for today; and here it is.

I need not tell folks in this neighbourhood that OUR Good Friday was a glorious day as to weather but as the Free Press goes to all parts of the world, I may for the instruction of old friends in America, India, Africa, Australia, New Zealand and the Hackney-Hockney Islands (I hope the boys will find them on the map); record the fact: It was a Good Friday of Good Fridays.

The sunshine went into the blood like wine. All nature drank it in and was gladdened, one could also see the buds expanding on the roses, the primrose gemmed every bank and the blue dog violets had burst into countless blossoms as if by magic, the pale anenome which I thought were never going to bloom at all this year, nodded in every brake and the air was full of that indescribable freshness and balminess and wake-you-up-and-make-you-grow-again peculiar to a fine spring day. The birds were engaged in a great singing match as I walked along and to my mind the thrush was getting the best of it.

You were bound to set off into the country somewhere, just as the swallows was bound to return and swirl over our heads with the warmth of Africa fresh upon his wings.

Off by carriage roads and by trains to all sorts of places. Off by ones and twos and threes and half dozens, walking along the roads and off some by water to Chapel Ed. Yes, by water. As I passed Pontymoile the air rang with music and there, gliding gently along the canal, in a gaily, decorated barge, were the band of the Cwmbran Rifle Volunteers, in uniform, with their wives and little ones, what could be more pleasant? Would it not be a treat if someone would get together a string of barges in the coming summer and offer the public the chance of a delicious ride along the placid waters to some sweet nooks on the bank? Why, we should have all of Blaenavon down to see the start and there would be fighting for the tickets.

I envied those Cwmbran people their voyage and was almost inclined to bid for a place amongst them, they floated on and I once more paused on the road to admire the beautiful wrought iron gates leading into the park. About these is a commonly received tale that the man who made them committed suicide because he found when he had finished them that he had omitted to make the parts agree and some difference in the arrangement of the clusters of grapes is pointed out in confirmation of this.

The romantic story will not bear investigation. Mr Jenkins, smith, now in the employ of Messrs Davies and Sandbrook, Crane Street, remembers that when a boy he worked on the gates of the premises of the late Mr Deakin, who then carried on business as an ironmonger near where Mr Lloyd’s pork butcher’s shop now stands, but I find, on further inquiry, that he could only have been engaged on certain alterations. These gates did not always wear their present appearance. The central gates (which are said to have been designed by Mr Nelmes) and surrounding monogram were given, together with the Russian marble mantelpiece in the dining room at the Park house, a service of plate and a set of jewels for Mrs Hanbury, by the celebrated Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, to Major John Hanbury (great-great-grandfather to the present Mr John Hanbury, the young squire,) M.P. for Monmouthshire, as a mark of her appreciation of the manner in which the Major discharged his trust as one of the executors under the will of the great Duke of Marlborough, John Churchill.

The Duke, who was born in a farmhouse which I have visited near Axminster in Devon and was not only the greatest warrior but the most fascinating mannered man of his day, died in 1722. Major Hanbury died in 1734. The renowned Duchess, familiarly called Sal Jennings, some of whose names were, if the anecdotes are to be trusted, exceedingly coarse and who used to domineer over the Queen Anne, addressing her plain as “Mrs Morley”, and being addressed by the Queen as “dear Mrs Free,” and survived until 1744. So the gates must have been presented between 1722 and 1734. They were erected between stone pillars, the present iron pillars which were cast at Blaendare furnace were substituted and the small side gates and grape decorations (it was the latter that were executed at Mr Deakin’s) were added within the memory of people still living. The handsome iron railings which enclose the park are said by some to have been made by the late Mr William Jarrett at the Park Forge (which stood within the Park, opposite Trosnant and close to the kennels and where the sheep were washed) but good authority ascribes them to the late Mr Henry Gunter, the estates smith.

On through the turnpike with the distant squawk of the cock pheasant sounding from the Park; on past the little church and it’s attendant public house (Llanvihangle Pontymoile and Horse and Jockey?) inseparable companions in certain districts where it is no uncommon thing for a funeral party to return home comfortably fuddled and to ease their feelings by singing hymns and comic songs alternatively over their ale; on past the big beech which similarly shaped like a couchant lion, crowns the summit of the entrance on my right; and I overtook a couple of youths who were stepping out as for dear life.

“Wither bound?” “Chapel-ed” of course. Everybody on that road went to Chapel-ed, except for two women and one gentleman and he would have gone there too if he could have got his tricycle up the hill but he couldn’t for his iron horse was to heavy to be carried or pushed and it had rather queer notions of the line of rectitude and it tumbled over with it’s rider twice when he, dead beat turned round and descended homewards.

Onwards and we came to the gateway of Col. Byrde’s mansion, just discernable through the leafless trees and shortly afterwards to the new school which that gentleman had been instrumental in erecting. It is a picturesque and commodious building and on the other side of the road has risen a smart shop, to be opened, I am told as an industrial store.

Col. Byrde’s house! and a blacksmiths shop! And a bridge! Let me stop a minute, Mr Blacksmith’s shop; for I think I have seen you before. Yes. You are the identical blacksmith’s shop at which I was directed to inquire my way the other day when I was puzzled by the labyrinth of lanes in my search for that renowned bone of contention – the Penystair Road. Ah! I knew where I was now.

That little house hard by where I saw the dancing last year. This was Pen….Pen….ten a penny? No, Pen….Pen….: I can’t get it out: those crack jaw welsh names were made for the people hereabouts and not for English tongues. A man learns for he know a little Latin, indeed? Let him try Welsh and say what he thinks of that.

A short lane, enlivened by the appearance of a professional beggar, a cripple who is transported from place to place lying on a donkey’s back and who exposes and thrusts his hideous and loathsome deformities in the face of every passer by brought me to Chapel–Ed itself.

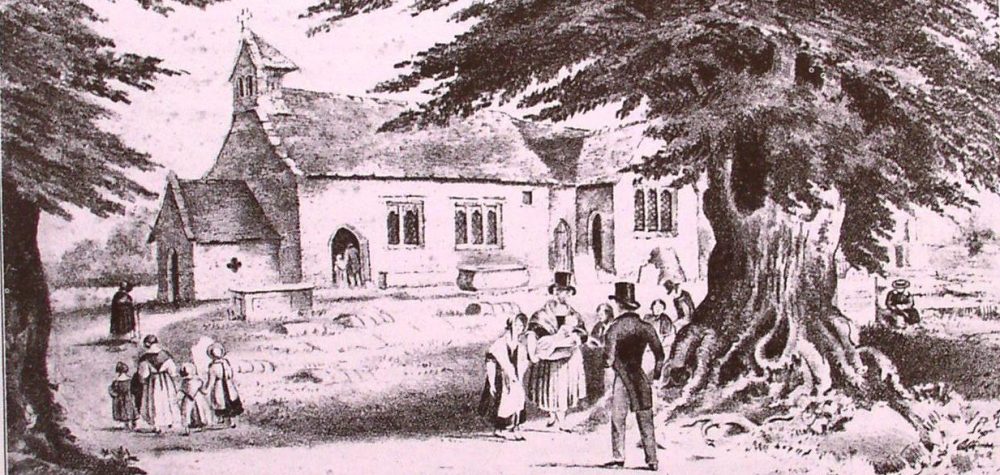

It is but a little place to make so much noise. A stranger would never guess that tiny prim and whitewashed Chapel in that quiet, out of the way lane has been esteemed the centre of a Saturnalia almost equal in debauchery to the sacred ancient mysteries. Yet, such is the ill-report had good ground in past years I cannot say. From conversations I am inclined to think it had but personal observation has convinced me that neither last year nor this year has the place deserved such sweeping censure that it is neither worse nor better that the usual run of pic-nic parities on a larger scale.

The religious observances are certainly not the great attraction at Chapel-ed, of the hundreds of young folks who trudge hither many never enter the Chapel at all except for the purpose of taking refreshment. They go rather for the sake of the amusements, most of them harmless enough; or, to use a popular term, for the sake of the “rigs” of Chapel – ed.

The tea drinking or “tea – fight,” in the chapel was by no means a solid undertaking. The exterior of the tiny edifice had been newly whitewashed and the interior had been decorated with pink and white paper, floral wreaths &c., and looked very smart indeed. Beneath the pulpit stood a very smart row of damsels busy engaged in pouring out tea, in front of them stood the minister, casting his eyes over the body of the chapel with evident satisfaction; the pews, arising one above one another, were crammed with tea drinkers; aloft at the back, was a body of matrons, whittling away at cakes and bread and butter as fast as their arms could go; and up and down the isles moved some good humoured young men waiters, who were certainly very attentive to the wants of the customers.

Long walks under the hot sun made people want refreshments; and the cheap ginger beer and oranges and nuts sold on the stall on the lane were not exactly all sufficient to satisfy the appetites of such an army.

Batches at a time took possession of the pews and some of them held possession of them a long time too. I wonder did anyone compute the utmost capacity of stowing away possessed by your thorough-going-tea-drinker? Dr. Johnson used to do great things in that way but I think some of these modern (advocates of temperance especially) could have beaten the doctor hollow and swallowed him afterwards, wig and all.

It would be ungallant to say anything about the ladies but I may say that I saw one gentleman that was busy with his (I will not pretend to say how many he had) cup when I went into the chapel and staid in after I left and who, when he did come out was red enough in the face to drive a bull mad and at least half corpulent again as usual.

I saw enter some extremely thin folk whose hungry looks meant business and I agree with the remark of a companion that it was well we had our shillings’ worth before their arrival. Whether they left any for anybody else we did not stop to see.

In the field outside the chapel hundreds of young of both sexes had assembled and a policeman was stationed there to prevent the awful wickedness of dancing. What wickedness there is in lightly touching a girl’s hand or waist, in the graceful figures of a quadrille than in running her down and tasting her lip in kiss-in-the-ring. I am at a loss to perceive and I don’t believe in it but I shall not attempt to argue the question.

If nothing worse than dancing had never gone on at Chapel-ed, the place would not have the unsavoury name it bears. Kiss-me-in-the-ring, elegantly termed by some of these present “slob chops” was in full swing and the looker – on learned a wrinkle as to how an entertaining and unscrupulous young man may keep the game alive and kiss every girl in the circle without receiving the inviting touch on the back from one of them. Racing, leaping and “tip-cat,” were also freely indulged and there were two or three fights, nipped in the bud by the approach of the policeman.

It is strange that some people cannot enjoy themselves unless they disturb the pleasure of everybody else. These cantankerous individuals ought, on approach of a festival, to be placed in straight waistcoats and kept at home, dosed alternatively with castor oil, asafoetida and brimstone and treacle, to cure their nasty tempers.

At Pen-what’s-his-name, dancing was not wicked. There the Cwmbran band had stationed themselves and were playing merrily and lads and lassies were footing it featly and decorously and tell it not in Gath! The Jack Jones’s and the Polly Morgan’s behaved very much like Duke’s sons and Bishop’s daughters at their hops (why apply a contemptuous term to the revels of one class more than to those of another?) in spended saloons.

For the credit of the band be it said that when they saw one unthinking youth (not a dancer and therefore, of concern, better than the dancers) commit a stupid act of wanton mischief, they pretty soon, like men and good citizens, told him their mind. The little public house itself was crammed in every room with men sipping and smoking, so crammed that some sat in the fire grates for want of other accommodation and there was a young man, with a strong facial resemblance to a clergyman with whom some of us know, solemnly stood up and sang a very long and rather doleful song and sang it very well too.

Outside there was one of those stands at which you shoot for nuts with curious guns that never will carry straight and with which you cannot hit the mark except by accident; a dilapidated individual who sold paper flowers sang “the last rose of summer,” abominably and vowed if there was a public house in a parish he was sure to find it and that he could smell it out if it were in the middle of a wood; and here again was that crippled beggar, disgusting everyone by exposing his monstrosities. This man ought to have been removed by the police. I pity his misfortunes as much as anyone can and say that he ought to be taken care of but he ought not to be permitted to outrage decency by forcing his hideous sight on the attention.

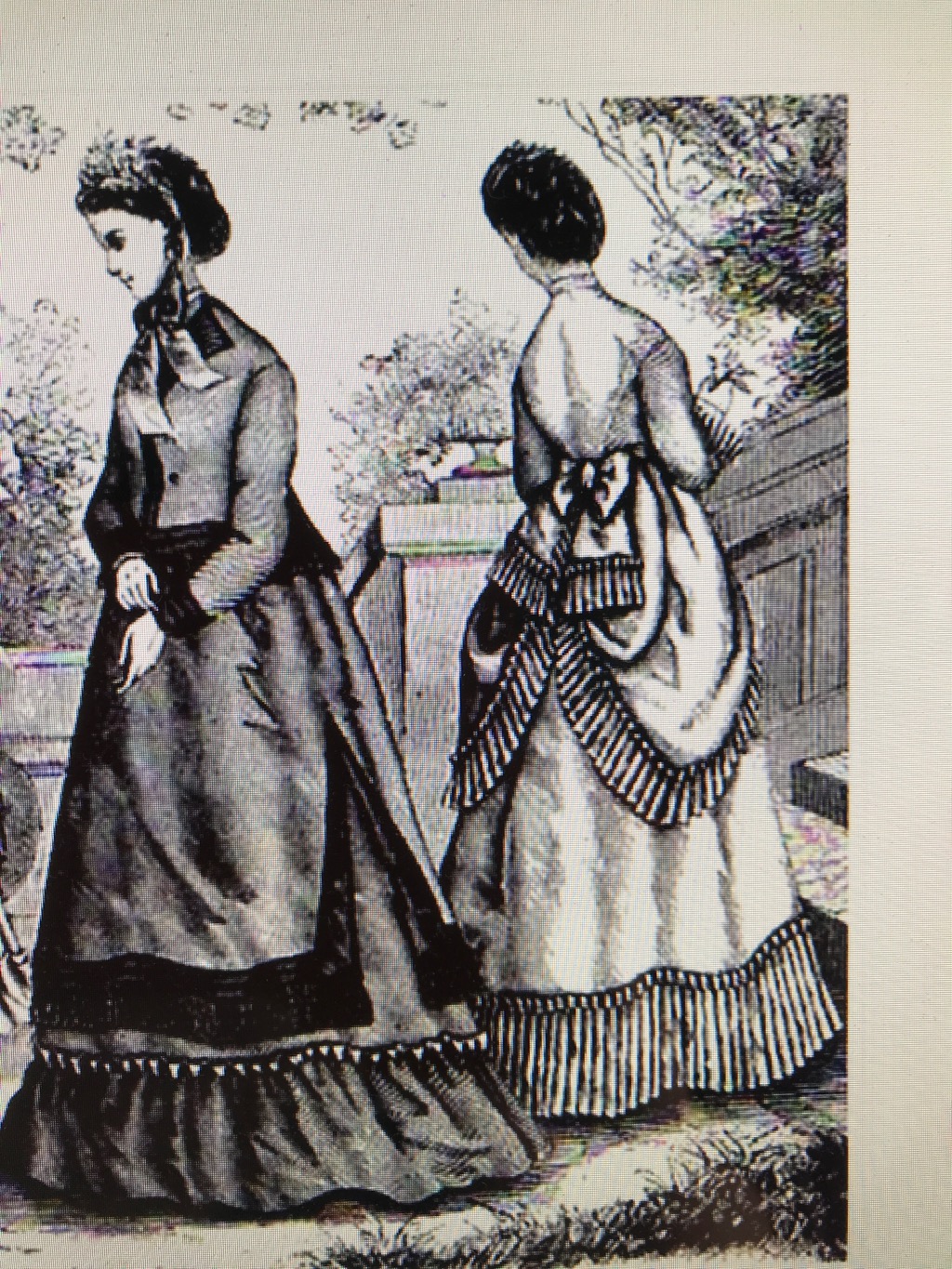

Returning to Chapel-Ed I found that kiss-in-the-ring was going on more enthusiastically than ever and perhaps some of the hunted and “slob-chopped” damsels were dressed very fine! Curious and wonderful are the fashions which take the feminine fancy! Very beautiful and in good taste and pleasing to an artists eye those monkey saddles behind, those strangely designed garments, those unnatural modes of wearing the hair with lumps of heaven-knows-what-and-where-it-came-from!

Even in this out of the way place were plenty of girls who sacrificed their natural grace and prettiness to the fashion. The limp is fashionable and wooden legs are likely to come in. Those choice get ups must have rather suffered from the racing, mauling and dragging they underwent.

The moon was now up and I threaded my way to Nantyderry station, the daffodils about which Herrick wrote the most exquisite and touching verses that were ever written about a flower, were hanging motionless in the silent brake; the brooklets ran glittering under the little wooden bridges; and that was all.

Oh! Chapel-ed! Chapel–ed! You must lose your character for naughtiness; and I hope you will never get it again! Your “rigs” are but tame “rigs” after all. There are no more real bogies about you than there are about the magnificent yew trees in Goytrey churchyard.

And what did I see at Nantyderry station? I saw some boys and girls listening to the strong humming of the telegraph wires in the breeze and heard the learned urchin of the lot tell the rest, speaking of the noise, that, “that was reading!” if it was, the words had got awfully mixed up together and he must be a clever fellow who could lick them apart.

I saw it raining pots and kettles and saucepans into the garden at the back of the refreshment room and thought that such practical joking might very well be let alone.

I heard that the said keeper of the refreshment room would do very well next year to have more assistants and look sharper after the money for his beer.

I saw that the stationmaster adopted a very well and creditable method of issuing tickets and admitting the passengers to the platform.

In the train and up the road to Pontypool I found that Abersychan folks can sing very well and as I entered the town I found that the performances were going on in Pinders Circus in Mr David Lewis’s steep meadow and admired the excellent playing of the band, not then aware that in those canvas walls was an old and accomplished friend whom I had not seen for nearly three years and who will no doubt be surprised to find I have linked him into my yarn about the “rigs of Chapel-ed.

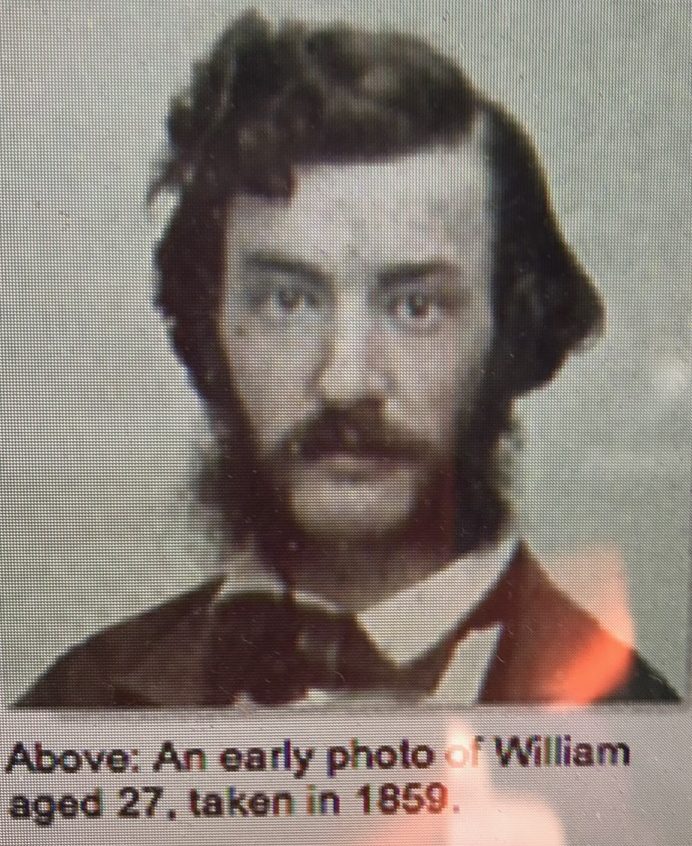

W H Greene