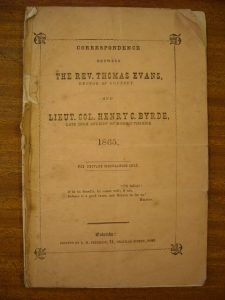

The following is printed in booklet form by Col Henry Byrde to be distributed amongst his friends. It began when Col. Byrde chose a friend to be his Chaplain when he was made High Sheriff of Monmouthshire in 1864 instead of the Rev. Thomas Evans. It was the cause of bad feeling between them which was never resolved.

Correspondence between The Rev Thomas Evans

Rector of Goytrey

AND

Lieut. Col. Henry Byrde

Late High Sherriff of Monmouthshire

1865

For Private Circulation Only

“I’ll hallod!!

if he be friendly he comes well; if not,

defence is a good cause and Heaven be for us.”

Introductory Remarks

Introductory Remarks

My Friends,

In requesting your perusal of a copy of a correspondence between the Rector of Goytrey and myself, I will ask your indulgence in making a few preliminary remarks in reference to the motives which have at length led me to submit it to you, and at the close I will add a brief explanation of one or two matters which have become mixed up with it.

It is generally known that the Rev. Mr Evans took offence at not being appointed my chaplain as High Sheriff of the County; – his letters to me on that subject are expressed in a very strong and offensive language, which he refused to retract, although assured that no slight was intended towards him in selecting another clergyman for the office; and he retains the same angry feeling that he shewed in the first instance, and neither time nor circumstances seem to have had any influence in lessening it.

So far, however, this disagreement between Mr. Evans and myself did not seem to call for that publicity which subsequently circumstances have forced upon me.

I refer to the fact, that members of my family and household have, by Mr Evans, during my absence, been excluded from the Sunday and weekly Schools in the Parish;- Schools composed in a great measure of the children of my Tenants and workmen, in which, with the full concurrence of Mr. Evans, all my family have taken an active and special interest, and I myself, been particularly identified; and I feel as if I continued separation from them was impossible, for the teaching in the Sunday school has been the joy and rejoicing of our hearts since we have resided at Goytrey, and we have had reason to think that our interest both in the weekly and Sunday schools has been valued by the Parents of the children, as well as a source of pleasure to the children themselves; while there never has been the slightest opposition to any desire expressed by Mr. or Mrs. Evans, but on the contrary a careful compliance with every wish made known by either of them.

So public an act as our ejection from the schools, under these circumstances, following Mr. Evans’s insulting letters to me, caused a feeling of just indignation on the part of members of my family, and a desire that I should explain to my friends the reason of this severance from the children of our parish, lest by remaining wholly silent, a misconception of the cause should obtain belief; and it can only be done by circulating among those esteem we value a copy of the correspondence referred to.

I should not, in the first instance, have made this correspondence known beyond the limits of my own family, out of deference to Mr. Evans position as clergyman of the Parish, had he not told some of the parishioners that I had quarrelled with him, and by this means attempted to throw responsibility on me which wholly appertained to himself, and, without an explanation, it might have been thought that this was the case, whereas the supposed grievance was entirely an imagination of his own, followed by a refusal to accept the assurance that no offence could have been intended.

With this notice of my motives in at length placing this correspondence before you, I need only ask your patient reading, to enlist your sympathy with the members of my family and myself in being so undeservedly subjected to such treatment.

The following is the correspondence referred to:-

No1. From Rev. T Evans to Lieut. Col. Byrde

Nanty Derri, 8th February, 1864

Dear Sir,

I will thank you to let me know what I am in your debt for the bricks, &c., which you were good enough to spare me; and also to let your Mason with Wm. Jones (Mason Burgwm) value the paving stones I had from you. I trust you will soon attend to this my request as under existing circumstances, which have necessarily destroyed all friendly and neighbourly intercourse between us, I am naturally anxious to discharge at once every obligation to you however trifling.

I remain, yours truly

(Signed) Thomas Evans

——————–

Answer No. 1 (From memory)

My Dear Mr. Evans,

I am quite at a loss to understand your note, and therefore address you as usual. Not being aware of any “existing circumstances” to destroy the friendly and neighbourly intercourse between us, I must beg for an explanation. I enclose a cheque for £4 as my school subscription, as I think it better to keep matters of this sort distinct from each other.

I am,

Yours Sincerely,

(Signed) Henry C Byrde

——————-

No. 2

Dear Sir, Nanty Derri February, 9th 1864

I am astonished you should have asked me for an explanation. I am the Clergyman of your Parish. Had I been appointed in 1863 and therefore a comparative stranger to you, had I been on bad terms with your family and yourself, had I rendered no services to you when it was impossible for you to serve yourself to the farms you now possess, I should not have felt so keenly the slight and public insult inflicted upon me by you in unconstitutionally passing by your own minister, and going to an adjoining Parish to select a Clergyman to officiate at the assize. If it be an honor to be selected for such a purpose, by the universal custom of the country, that honor is due to the Clergyman of the Parish wherein the Sheriff resides, unless a Clerical relation should be in the way, having the claims of consanguinity. Not that I craved the compliment, far from it.

I should have deemed the duties in some measure inconvenient. But I do care to find a Parishioner so utterly wanting in the common respect due to his parochial minister as you considered you to be incapable of doing. On Saturday evening your aunt, without a single comment on the subject asked me, who I thought was your chaplain, I said “Walter Marriott of course.” Having received no intimation of your intention, the natural conclusion I drew was that either Mr. Marriott or Mr. John Mais had been fixed on. On hearing that the neighbouring Clergyman was fixed on because he was an old friend, my poor wife, who said nothing, who has said nothing since, turned as pale as death, and felt as I did, that Col. Byrde ought to be the last man to treat her husband with such indignity. I never mentioned the subject to my wife, nor does she know anything about my communication to you. This circumstance is the greatest mortification she ever had and certainly the most humbling and painful one I ever endured, and it is the more keenly felt because it is occasioned by one from whom I had a right to expect at least exemption from a public slight, a slight in the county where I am pretty well known as the Rector of Goytrey, where Goytrey House is situate.

Had you fixed on a relative, my feelings would have been spared and you would have preserved an outward consistency, and shewn that according to the spirit of your Master you “know him who labours among you, and is over you in the Lord” &c. I want no praise, but what by custom is my due. I am aware that some do pass by their Clergyman of their own parishes in this way, this however is the exception and not the rule, and where it is the case, it is traceable to some paltry private pique, or to the reasons referred to. After so unfriendly, un-neighbourly, unchristian and unfeeling act on your part, to use a common term a cut in the most public manner possible, it is utterly impossible that any friendly intercourse can ever again subsist between us.

The insult I will bear as a Christian, and trust in the spirit of my Divine Master, and will not I hope resent it with any bitterness, but will feel it to be a duty I owe to myself as a man and a gentleman, and to my position as the Clergyman of the parish, to mark it with lasting censure and condemnation and to regard it as the strongest proof that could be given that Col. Byrde was my neighbour, my parishioner, my communicant, in a certain sense, but never in my sense a real friend of mine.

Words would not have been plainer, than those used by you at our station as regarded the full and fair share of your liability in securing £30 per annum for Mr. Whitmarsh, cottage included. I have acted as collector and paymaster. The receipt of £4 is therefore on account. Should you write to me again I shall thank you to do so by Post on account of my wife, who must not be excited.

Yours truly,

Thomas Evans

Answer No.2. – Goytrey House, February 10th 1864

Revd. Sir,

I was perfectly amazed at the subject and tenor of the note I received from you yesterday. You have not asked me for any explanation of a supposed “slight” and “insult”, but on the contrary the decisive terms in which you have announced the termination for ever of any friendly intercourse, naturally precludes any further reference to the subject which has called forth so abrupt a decision on your part. I am nevertheless actuated by a sense of duty to myself to counter the explanation that might have been asked previous to your condemnation, as well as to remove from your mind, if possible, the erroneous assumption that any slight or insult could have possibly been intended by me. In the first place when the Deputy Sheriff was asked, whom it was usual to appoint as chaplain, he replied that it was quite optional, and instanced the late Sheriff who selected an old school fellow, I expressed the strong desire I entertained to pay a tribute of respect to one friend of my youth living here, and he at once said that I could not, under the circumstances, make a more appropriate selection.

Had I known it was customary to select the Clergyman of the parish I would have explained to you the peculiar circumstances under which I was induced to set aside even the claims of consanguinity, in the choice I had made; at the same time you are fully aware of the strong feeling of attachment subsisting between Gardner and myself, and must approve of the motives which actuated me in selecting him, as you well know he was the only one near my own age, who during my sojourn in Goytrey, in my youth, thought it worth while to cultivate my friendship, and with the exception of Mr Grieve’s family I may say with justice, that but for Gardner I should have been without a friend, beyond the range of my own family.

This claim on me therefore was of so sacred a nature that it could not be set aside with propriety, and I should have thought that such a sentiment would have found a responsive echo in your own breast, instead of the unmitigated censure the supposed neglect of yourself has called forth: – That I have not forgotten an older friend than yourself, and friendship formed under peculiar circumstances should have been an earnest to you, that I was not unmindful of such sentiments, and I cannot avoid the conclusion forced upon me that the friendship you professed must have rested on a very shallow foundation, to have been so readily, so summarily, and so irrevocably terminated.

I remain, Revd. Sir,

Yours faithfully,

Signed Henry C Byrde.

P.S. In sending my usual subscription to the School I had no intention to depart from the pledge I gave to share the deficiency of salary guaranteed to Mr Whitmarsh.

No.3 – Nanty derri February 11th 1864

Dear Sir,

I have read your letter of explanation. You could not have been ignorant of the fact that your passing by of your own Clergyman not withstanding the circumstances referred to, and which gave him a special claim on you, was a departure from propriety, and a violation if that feeling of common respect and courtesy which in all civilised society I had a right, as the parish priest to expect from a parishioner. The choice, of course, is, and must be optional. But you are not ignorant of what is due from one Gentleman to another, and what is proper and right, and what you would consider due to yourself if you were in my place.

If you had an ardent longing to bestow the honour on your very old friend (whom I do not blame, whom I respect) the least you could have done was to express to me that longing on your part. I was not before now aware that your friendship for Mr. Gardner was of so very “sacred a nature” that you could not with propriety set him aside, rather his claim!

He has of course laboured for you, travelled about the country for you, spent much of his valuable time in your service, taxed his brains in writing to Mr. Mais, to London lawyers, to Mr. Jones of Clythas agent and others, negotiated with award vendors, in short has acted for a considerable period as your faithful agent most disinterestedly and zealously, and with such success as rejoiced your heart, and secured for you through dint of perseverance the broad acres in Goytrey that now give you as you consider, great local importance: having been thus so generously served by Mr Gardner, it would certainly have been the height of ingratitude in you to have withheld from him the tribute of respect which he so deservedly earned.

Having given you in deeds, and such deeds which in every respect are far more valuable than words, proofs of real not “shallow friend-ship”, you could not, I must admit, think for an instant, of ignoring so “sacred a friend-ship” that has so materially and favourably told on your position and importance in the parish and county, and of returning to him evil for his disinterested good to you.

Men are sometimes actuated by motives that are obvious on the surface, and sometimes by motives and feelings that are deep in the strong under-current. It is observed by a Divine, that he had never seen in the long run a lasting blessing on those who are capable of, and guilty of, slighting and deprecating by word or deed, one, who in the Providence of God is appointed to minister to them in holy things.

Yours faithfully,

(Signed) Thomas Evans

No.3 Nantyderri, January 9th 1865

Sir,

I beg to remind you that your subscription to the school for 1864 is not yet received and that the account referred to in the correspondence of February last is still unsettled. At your wife’s request, I paid for you a subscription of £1. 1. 0 to the Bible Society Auxiliary at Llanover. As you have shown and may yet shew the correspondence, truth and justice to myself demand that I should notice an expression in your last letter which escaped my observation at the time, and which seems to me calculated to convey an insinuation inconsistent with fact.

It is this “I should have thought that such considerations would have found a responsive echo in your own great” &c. When I lived some eight months with my brother and guardian who was the clergyman here, and subsequently in the neighbourhood, I am not aware that I was specially in-debted to any people (out of my own family) for their thinking it worth their while to cultivate an acquaintance, which as the minister’s brother I naturally formed in the parish and neighbourhood, nor am I conscious of having received at any time any particular favours or patronage, except from the late Earl of Abergavenny. When you next exhibit the letters (to this I have no objection) I trust your sense of justice will induce you to show this also.

I am Sir,

Your Obedient Servant,

(Signed) Thomas Evans

To The Rev. T. Evans

Answer No.3 – Steamer Nyanza, January 18th 1864

Sir, – Having received your note just on the eve of leaving home, I was unable to do more than hurriedly send Mrs Byrde’s donation to the Bible Society and my annual subscription to the school, and whatever may be further due on the latter account I shall be prepared to pay on being furnished with a statement of the account.

I did not bring your note with me, but if my memory of its contents is correct, you refer to the following expression which I made use of it in reference to the exercise of the motives which actuated my own conduct viz.”which I should have thought would have found a responsive echo in your own breast.”

The meaning contended to be conveyed being simply that which the words themselves imply: that I had given you credit for appreciating generous motives, as well as candour or accepting the assurance of them, though to my disappointment, I have subsequently found that you were incapable of either.

I can have no possible objection exhibiting or even publishing, should it be necessary, your last note, and this reply with the previous correspondence,

I am Sir,

Your obedient servant,

(Signed) Henry C Byrde

Copy of the Rev. T. Evans note to R.A. Byrde – Nanty Derri February 9th 1865

Sir, – In consequence of the rupture between me and your father and of which there is no prospect of its being healed, co-operation is become impracticable. Therefore it would be folly to put up a Finger Organ in the Gallery of Goytrey Church. I have therefore decided upon not allowing the Finger Organ to be put up and shall only retain the Seraphine which can be played under all circumstance.

I am Sir,

Yours Truly,

(Signed) Thomas Evans,

Rector of Goytrey

Rev T. Evans reply to letter of 18th Jane. 1865

No 4. Nanty Derri, February 14th 1865

Sir, – Whatever meaning you attach to the words “responsive echo in your own breast” I maintain they are capable of being understood in the sense which I attached to them as being possible to be their meaning.

When equivocal language is used the writer must be prepared to receive a reply according to the various interpretations his words may bear, and my reply to this part of his letter has been more sparing than it might have been.

There may be distinctions here that I cannot unravel, a refinement of emotion which perhaps I am not able to fathom. But I hope with all my dullness that I am incapable of being blinded by plausibility. I hope I shall always be able to distinguish between pretence and reality, and between hypocrisy and sincerity; although I have not been abroad as you have been, still my knowledge of human nature is I trust, sufficient to detect affection, awesomeness and dissimulation.

I am reflected upon deeply in your last letter as to my capacity, and seems to be regarded more as a school boy than as a man or a minister. Be it so, I acknowledge my incapacity to under stand the matter in the extraordinary light in which you seem delirious to put it. It will take a long time to satisfy any man of common sense that there was any generosity of sentiment involved in the act of passing by your own Clergyman and appointing Mr. Gardner, particularly when that Clergyman had proved such a substantial friend in your absence. I acknowledge it was a kind of weakness in me to have written or said a word to you about it. I would have been perhaps more becoming in me and more dignified to have treated it with silent contempt, as clergymen do in general under such circumstances. My weakness however in this behalf will show perhaps that I am not so deficient in candour as you insinuate in your last.

To me indeed it would have been a burden and a nuisance to have been engaged as chaplain of the High Sheriff. Most probably I should have thought it necessary to decline it, had it been offered to me.

My fortune and position, I am thankful to say, are such that I could have nothing whatever to gain by an exhibition of myself on such an occasion, and what led me to notice the matter at all in my letter to you was that I could not brook dissimulation.

The entire absence of candour and generosity of sentiment as it appeared to me, and above all, of common gratitude in the transition was such as I thought at the time demanded of me either some written or verbal notice of it to yourself. When I at your special request from Ceylon devoted my time and attention for years in effecting the purchase of farms for you in Goytrey, many if not most of them still with or on heavy mortgages, indeed to the increase of the coolness which unfortunately but causelessly on my part existed between me and Lord Llanover, I was at a loss what motive could have induced you, under such circumstances to slight or pass over me, unless it was because you thought you might please Lord Llanover by it, or displease him by appointing me.

Whatever your motives were, it matters not to me, and I do not care what they were. But I look at the act itself. Ancient and “sacred friendship” has been put forward very emphatically in this correspondence, and in a very imposing manner. Mr. Gardner was known to you it seems 8 or 10 years perhaps before I was; as you have urged this point so very carefully that he was the friend of your youth &c., it is, I think a great pity that the people of this country do not give you credit for it, as none of them had ever observed or known of this extraordinary friendship. I can’t help it that they don’t , and if I am one of those unbelievers you must not blame me, for we all require in such cases not mere assertion but proofs. Indeed the proofs seem to be quite the other way, for I heard repeatedly members of your own family, when I boarded with them now more than 20 years ago, and with whom you yourself lived in your youth, say that they heard you frequently express a dislike* of Mr. Gardner and your words in those times as they are repeated to me I could quote if necessary at the present moment. So much for the ancient and sacred friendship so gravely put forward as an excuse.

I have given strict orders that no erections for the future of any sort are to be made in the church without my knowledge or concurrence, and I have written to your son to decline having a finger organ put up in the church instead of a Seraphine. Perhaps you think you might appear to great advantage before the public if all this correspondence were published, perhaps you are greatly mistaken herein, and after the receipt of this you will probably feel less disposed to have our correspondence published. For my own part I only intended it as a private communication between ourselves, an explanation of my first letter, at your request. I therefore though not afraid of you, decline becoming a public correspondence of yours, and decline any further correspondence or intercourse with you in any shape or form. I will give orders to Mr. Whitmarsh to supply you with the school account for the future, and am.

Yours truly,

(Signed) Thomas Evans

Note:- Not true that I so expressed myself, or ever entertained such a feeling. – H.C.B.

To the Right Reverend. The Lord Bishop of Llandaff. Kandy, Ceylon, February, 28th 1865

My dear Lord,

I must beg you to permit an explanation of an inadvertency on the part of my step-father in forwarding to your Lordship a correspondence between the Rector of Goytrey and myself without the letter of explanation which was to have accompanied it, and which I had promised to send him for that purpose, whereas under the supposition that I had addresses your Lordship direct, he forwarded the correspondence without waiting for my communication.

An apology is also due to your Lordship for troubling you with a matter rather of private than of public interest, but so intimately connected with the well-being of the church of which I and my family are members, and of which your Lordship is the Spiritual Head, and with that of the Parish in which I reside, that I feel it due to myself and to them to represent the difficulty in which we are placed by the uncalled for conduct of the Rector of the Parish towards me.

I also feel it due to your Lordship to lay this grievance before you not so much for any remedy which you might be able to apply, but rather to enlist your sympathy with the uncomfortable position in which my family have by this means have been placed.

I have an aged mother residing with me who is unable to attend the ministrations of the Church and an invalid son is similarly circumstanced, and there is a natural delicacy in asking on our part, or in acceding to a request for spiritual ministrations by neighbouring clergymen, and several members of my family as well as some of my dependants feel debarred from participating in the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper at the hands of a clergyman who has evidenced, and continues to manifest, so hostile a feeling.

I am also desirous that your Lordship should be rightly informed on a matter which might otherwise lead to the conclusion that I had by some misconduct or other improper manner alienated the affection and friendship of the Rector of my Parish from myself and my family.

I will not deny that before I resided in Goytrey my representative was indebted to Mr. Evans, for some aid in the purchase of lands in the parish, and I have always expressed and endeavoured to show my sense of obligation for this assistance, and this has withheld me from even noticing several instances of unfriendliness and absence of confidence on the part of Mr. Evans, since I resided in his parish, with which, however, and other matters referring to Mr. Evans I refrain from troubling your Lordship, nor could I now have been induced to address you on so painful a subject but from a sense of duty I owe to the position, I had the honour to occupy as High Sheriff, and in justice to the several members of my family who occupy my residence.

I had hoped that, before I left England last month for a temporary residence in Ceylon, the assurance conveyed in my letter would, at length, have elicited some advance to a reconciliation on his part which would have spared me the pain of such communication as the present, but I regret to say that the same feeling as that expressed in his letter continued to be manifested by Mr. Evans on every available occasion.

I need hardly assure your Lordship that so far from mediating any possible slight towards Mr. Evans in soliciting another Clergyman to be my chaplain, I was so utterly unconscious of wounding his feelings that I could not imagine the cause of his first note to me, nor could any member of my family, and I never even imagined he would have valued the office, especially as he had announced his intentions of being absent in London for some weeks at the period of the assizes.

My reluctance in making this communication at all, has been the cause of the long delay in addressing your Lordship on the subject.

I remain, My Dear Lord,

Yours very faithfully

(Signed) Henry C. Byrde

11. To Lieut. Col. H. C. Byrde. – Bishop’s Court Llandaff – April 7th 1865

My Dear Sir,

A few days ago I received the letter which you did me the favour of writing to me on March 1st. The packet of correspondence between yourself and the Revd. T. Evans had reached me in the month of January, but as no statement accompanied it, I could only conjecture from whom it came and for what motive it was sent. I do not hesitate to say that I read it with great regret, and that in my opinion Mr. Evans is entirely in the wrong as to the assumption that the fact of your not appointing him your Chaplain implied an intention to insult him. Further than this I form no judgement as to the relations that have subsisted between him and yourself, for I am without any knowledge of circumstances, and should not wish to come to any conclusion upon an expert statement on one side or on the other.

On the receipt of your letter of March 1st, I wrote to Mr. Evans to the above effect saying also that if I were in his place I should not hesitate to ask you to consider my letters as never having been written, and to apologise for the tune I had assumed. I added that I was quite sure he would in no way impair his dignity by so doing, and hinted that he should consider his position as the Christian Pastor of the Parish to which you belonged, I made also some extracts from your letter in which you positively repudiate the intentions of hurting his feelings.

You will, I trust, see that I have done all I could. His reply I am sorry to say, is not what I hoped and desired. He declines to comply with my advice. This conclusion I greatly regret, but however I may lament it, it is obviously a matter beyond my control. If a Clergyman thinks himself affronted, it is not an ecclesiastical offence, and if he thinks himself justified in declining to act upon his Bishop’s advice, the Bishop having no jurisdiction in such a matter, can do no more.

I can only therefore inform you of what has happened so far as I am concerned, and express my sorrow that I cannot send you a more welcome communication.

I remain, Dear Sir,

Yours faithfully,

(Signed) A. Llandaff.

This closed the correspondence with Mr. Evans.

The following is an extract from a letter from my sister now residing at Goytrey.

On Saturday evening a note from Mr. Evans was put into my hands the following is a copy.

Nanty derri House June 3rd 1865

Madam,

I regret much to be compelled to intrude upon you the subject matter of this note. I can truly say that I regret the more because in all your endeavours for the success of the Sunday school you have shown commendable zeal, and perseverance. It is however my plain duty to be candid and explicit and convey to you my views and feelings. I have felt that the circumstances to which I need not allude has materially interfered with, I may say rendered it impossible that supervision of my Sunday school which before your brother came to reside in the parish I was in the habit of exercising over it as the Clergyman. Upon a careful and I can add serious consideration of the subject I have come to the conclusion that it is my bounden duty not to allow myself to remain any longer in an awkward position with respect to the Sunday and weekly schools. I am therefore under the self-denying necessity of foregoing for the future the advantage derived by the children thus far from the attendance of yourself and Miss Grieve or any member of your family. I beg to thank you and Miss Grieve for the kind and efficient services you have rendered the school.

The box containing your brother’s books I now send, having replaced it by another containing books of my own selection. I find the club money is £1. 7. 0. or thereabouts. I am prepared to continue the club so that the children shall not lose anything by the change, and the service hitherto so kindly rendered by Miss Grieve in the week will be performed by another person.

Thanking you again for the aid you have given which has not been unappreciated by me and trusting you will receive this communication in the spirit and christian feeling in which it was penned.

I remain Madam,

Yours truly,

(Signed) Thomas Evans.

Concluding Observations – In explanation of the foregoing I will offer a few remarks.

On receipt of Mr. Evans’s first note I was puzzled to imagine what could have happened to “destroy all friendly and neighbourly intercourse,” so little did I or any of my family dream of the cause of such a letter, and had Mr. Evans expressed himself clearly I should have tendered any explanation in my power to sooth his feelings, but under the circumstances, I could only write a friendly note in the usual terms of address. I may remark that I had the previous day spent the time between the afternoon school and the evening service at his house, and there being no difference in my cordiality of manner, he should have been satisfied that I could had no intention of slighting him.

I was therefore beyond measure surprised at Mr. Evans’s letter of 9th February and could hardly believe that I was reading a communication from him, and the members of my family were as much astonished at its tenor as I was, myself.

To accuse me of “unfriendly, unneighbourly, unchristian and unfeeling” conduct without ever asking for an explanation, and to say that it was utterly impossible that any friendly intercourse could ever again subsist between us, and marking the supposed slight of himself with his “lasting censure and condemnation,” was very strong language for a clergyman to use towards a member of his congregation who had always been on friendly terms with him, and such as only the most aggravating circumstances could justify.

I hoped his feeling of irritation would have been soothed when I volunteered the explanation contained in my letter of February 10th, and that he would have recalled the severe “censure and condemnation” he had denounced against me when assured that it was as undeserved on my part as the sentence of condemnation was unmitigated on his.

In order that it may not be thought that Mr. Evans was correct in supposing that it was the custom for the Clergyman of the Parish to be selected by the Sheriff for the office of Chaplain I must explain that an enquiry into the appointments that have been made for several years past has proved that the selections of the greater number of Chaplains by the Sheriff of Monmouthshire have not been the Clergyman of their own Parishes, and in exercising my right of choice in favour of a very old friend no indignity could possibly be cast upon Mr. Evans.

On referring to my letter you will see that I avoided every expression that could cause further irritation although I felt grieved at having even unintentionally given offence, and very sorely hurt at the strong terms used by Mr Evans, but I hoped that my explanation would have been met in a candid spirit, and have had the effect of leading to a right understanding.

You will, no doubt have been surprised at Mr. Evans’s reply. The style of his letter is intended to be sarcastic in pretending to detail the services that Mr. Gardner rendered to me to entitle him to my friendship and favour in the appointment of Chaplain instead of himself. Added to which the insinuation that I did not adhere to the truth when endeavouring to explain my reasons for the course which I had adopted, convinced me, that it was useless to continue a correspondence with him, even if he had not himself prohibited any further intercourse.

I would not attempt to disparage any services rendered to me by Mr. Evans and I always gave him credit for having aided my representative in purchasing property for me and I have given proofs that I was not unmindful of his assistance, but until reminded of it, I had not been aware of the amount of obligation I was under in this behalf.

Mr. Evans ignores obligation to any member of my family although I carefully refrained from such an insinuation.

In submitting the correspondence to the Bishop of the Diocese a hope was entertained that through his influence, some better understanding might have been brought about. His Lordship’s reply communicating the result speaks for itself. A Clergyman who could behave in this manner towards an unoffending parishioner would not be very ready to listen to the remonstrance and advice of even his Bishop.

I have been at a loss to understand what Mr. Evans refers to when he says he has given “Strict orders that no erections of any sort to be made in the church without his knowledge and concurrence.”

He may refer to our “family pew” which was made as early as possible to resemble the old one when the Church was rebuilt, as the arrangement admitted, and which was approved by me, under his and the Church wardens sanction some four or five years ago, and which he has now entirely altered, having removed my improvements and changed the original construction without any apparent object, and without reference to me or my family.

Or Mr. Evans may allude to the Monument, now completed, which I expressed an intention of placing in the Church in memory of my Father. Of this however he has left me in doubt, though his remarks appear to point to this object. Or he may refer to the “organ” for which one of my sons has collected subscriptions, and which was about to be erected in the church, except that he makes separate mention of this in one of his letters.

I have therefore been left in doubt to which he refers. The Pew, Monument, or the Organ.

I trust I have not been altogether regardless of the sacred injunction. “If it be possible, as much as Leith in you, live peaceably with all men,” nor have I, I hope, been wholly unmindful of the admonition to “render to all their dues,” but I have failed to discover how I could have acted otherwise than I did, when I offered, unasked, an explanation of an imagined offence that should, at least, have led, on the part of a Christian Minister, to an amicable reply.

Henry C. Byrde.